Carlo (that’s me) doesn’t know how to read.

How do you read? How do I read?

Carlo reads by creating pictures in his mind which convey the meaning of the work he is reading. For him, at least, what he reads becomes a series of symbols which act as concrete signposts designating the important parts of the work – again, for him. One memorable scene in Giulio Mozzi’s Carlo Doesn’t Know How to Read has Carlo talking at length at a book reading by one of his favourite authors about a scene in which the pocket of a raincoat has its stitching come undone – a scene which is, to the other readers, and to the author, forgettable, indeed unimportant: but for Carlo, who sees the scene so emphatic and clear, it has become paramount.

Carlo doesn’t recognise words because he doesn’t see them. If the page includes the word “door,” Carlo doesn’t the word “door.” He sees a door. If the page includes the word “blue,” Carlo doesn’t see the word “blue”. He sees something blue.

I have friends who read novels as though they are movies transferred to text. They create “moving pictures” in their head, vast, bright, elaborate scenes involving characters, plot and excitement. Perhaps this automatic response of creating a movie in their mind comes from the fact that they have been raised with television and cinema as their primary method of consuming entertainment, or perhaps some novels naturally align themselves with the expositionary and visually kinetic functions of cinema.

I have always found it bewildering when a friend tells me that a book they have enjoyed has played out, for them, like a high-impact, high-budget movie in their heads, with action, drama, sex, twists, and adventure. They have, always and without question, a firm picture in their mind as to how the lead character looks (assisted, no doubt, by the author’s own descriptions), as well as how the story itself unfolds. How, then, do I read? Not like that. I never form an understanding of the character’s appearance – no matter how many times the author might describe their characters, I forget instantaneously. I never picture scenes, nor allow the creation of a space in my mind where the action might unfold. The reading of writing is, for me, an exercise in understanding the structure and make-up of a text, its effects and the subtle selection of words and phrases with which a novel is created. I examine the scaffolding and admire the facade, and always, always, attempt to locate the cracks and joins of the piece, both to admire and to critique. Reading, no matter its pleasures, has become an exercise in professional examination as much as enjoyment.

When he tells his friends about a book…Carlo imagines himself reentering the space where he was the first time he read the book, and from there, withing that space, the action going on around him, Carlo looks all over, looks at things, notes what’s there, what he didn’t notice before when he was reading, and he names these things, comes up with words – apparently, for Carlo, spoken words are completely different from written words – and so as he sees these things, bit by bit, he realises that they’re there.

Which type of reading is better? It’s hard – perhaps impossible – to say. I prefer my own method, but of course that is because it is the method I employ. Creating a movie in my head seems, to me, to be a side-step away from literature, to admit that the written word is in fact subordinate to cinema, that literature’s function is to act now as a more quiet, more personal example of the blockbuster. Virtually every writer I read would be unfilmable if this were the case, and all of the writers I hold dear to my heart are untranslatable to any other medium – they are literature, they are not film, nor music, nor song, nor photography. I could hardly create a film of Sebald’s Vertigo or Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives, or Vila-Matas’ Montano’s Malady in my mind – it wouldn’t make sense, the thrust and central conceits of these works wouldn’t transfer, the art of the work would fail.

”When you talk about a book,” one friend told him, “it’s like you’re talking about a dream. And it’s always hard to tell with dreams if you’re describing what you saw or if the act of trying to describe a dream has set your imagination off in a new direction so that now you’re actually adding new things to what you remember…

What, then, is reading? Is it an exercise in understanding the machinations of a master craftsman? To perceive it in that manner may assist in one’s own writing but it makes of literature a kind of examinatory archaeology, as though writers scrounge around in the skeletons of other works in the hopes of learning choice tidbits for their own use while forgoing the beauty of what they have discovered. I am a lesser reader if I read, say, Borges purely for his technique – I must also read him for his art, his feeling, his successes and his failures. Writing cannot stand purely on its technical merit, or its place in literary history. Writing does not stand purely on its technical merit, or its place in literary history. It is, instead, a series of conversations by the worlds most insightful, most empathic, most intellectual men and women discussing the most difficult concepts with one another. I am reminded here of E. M. Forster’s conception of the great writers of the world assembled around a large circular table, writing and discussing in competition with one another – that is, not with their milieu, or their generation, or their style, or their genre, but with one another. But writing is also the examination of beautiful things, of wonderful ideas, of hopeless ambitions and crusades, and of the tiny, the insignificant, the small, The purview of the writer is enormous – it is as much, or as little, as the writer would like. Their mandate is what they decide, no more and no less.

What, then, is reading? It is not a smaller, quieter substitute for cinema, though certain books may function as such. A novel offers the reader a window not only to another time or place or sensation or feeling, but allows a viewpoint into the prejudices, intellect and emotion of another person, another intellect. We are able to come as close to understanding another person when we read the best that they are capable of writing, because a (very) good book should be the purest and clearest expression of the author’s intention – the author’s idealistic self. To read is to experience the aesthetic appreciation of the author’s entire world condensed into a cohesive expression.

…there’s no question that these are always the same things, the things that make up the story, the objects and things that motivate the action going on in the story; and yet they’re never really the exact same things: a door’s a door but never the same door; an evening’s an evening but never the same evening; a kitchen table’s a kitchen table but never the same kitchen table… And even Carlo, his friends realize, when they meet for one of their evenings at the bar by the Poggio Rusco station, even Carlo’s not the same exact Carlo; no, he’s really not the same Carlo; he’s always a Carlo but never the same Carlo..

This review has avoided discussing the construction of Giulio Mozzi’s Carlo Doesn’t Know How to Read to instead examine the questions it raises. The story itself is of little consequence – there is virtually no plot to speak of, and no character, either. “Carlo” is a stand-in for Mozzi (and indeed, this story was originally portrayed as written by “Carlo Dalcielo”, who turned out to be a fictional creation of Mozzi’s), and the story itself is a stand-in for an essay on reading, writing, and the effects of both on the writer and the reader. This is a story which forces one to examine their reasons for reading and how they read, and whether their method of reading is the most appropriate both for themselves and for the piece in question (whatever that piece may be).

Carlo Doesn’t Know How to Read by Giulio Mozzi is a short story from the Dalkey Archive Press’ anthology, Best European Fiction 2010

di Giorgio Falco

[Questo articolo è apparso in Repubblica l’11 febbraio 2010]

Otto chilometri a nord di Reggio Emilia, c’è un paese di novemila abitanti, Bagnolo in Piano. E’ probabile che i bagnolesi non sappiano di avere tra i loro nati uno scrittore, scelto per rappresentare l’Italia nell’antologia Best European Fiction 2010, pubblicata dalla casa editrice statunitense Dalkey Archive Press. Carlo Dalcielo è nato a Bagnolo in Piano nel 1980. L’ospedale in quel comune non è mai esistito e gli altri scarni dati biografici – reperiti da una mia chiacchierata amichevole con don Eugenio, l’anziano sacerdote della parrocchia di San Quirino, – confermano soltanto che la zia, Wilma Dalcielo, sorella di Mario, padre di Carlo, lavorava come ostetrica presso l’ospedale di Reggio Emilia, e proprio zia Wilma, oggi pensionata, pare abbia assistito Anna, madre di Carlo, nel parto a domicilio.

Otto chilometri a nord di Reggio Emilia, c’è un paese di novemila abitanti, Bagnolo in Piano. E’ probabile che i bagnolesi non sappiano di avere tra i loro nati uno scrittore, scelto per rappresentare l’Italia nell’antologia Best European Fiction 2010, pubblicata dalla casa editrice statunitense Dalkey Archive Press. Carlo Dalcielo è nato a Bagnolo in Piano nel 1980. L’ospedale in quel comune non è mai esistito e gli altri scarni dati biografici – reperiti da una mia chiacchierata amichevole con don Eugenio, l’anziano sacerdote della parrocchia di San Quirino, – confermano soltanto che la zia, Wilma Dalcielo, sorella di Mario, padre di Carlo, lavorava come ostetrica presso l’ospedale di Reggio Emilia, e proprio zia Wilma, oggi pensionata, pare abbia assistito Anna, madre di Carlo, nel parto a domicilio.

Nel 1998 Carlo Dalcielo è ufficialmente rinato dalla collaborazione tra l’artista Bruno Lorini e lo scrittore Giulio Mozzi. Dalcielo debutta in Fiction (Einaudi, 2001), quando ha preso la parola sottraendola a un Mozzi particolarmente prolifico in quel periodo. Da allora, Dalcielo ha continuato a scrivere, esposto in gallerie nazionali ed estere, nel 2008 ha pubblicato un libro anomalo, omaggio a Carver nel ventennale della morte: Il pittore e il pesce (minimum fax). Proprio il contributo narrativo di Dalcielo, intitolato Carlo non sa leggere, è stato scelto e ripubblicato nell’antologia citata.

Quando ho visto l’indice del libro, sono rimasto sorpreso, perché l’editore e il curatore Aleksandar Hemon hanno inserito Giulio Mozzi (Aka Carlo Dalcielo). Ecco, Also known as, messo tra parentesi, mi è parso ingeneroso verso Carlo Dalcielo, equiparato a uno pseudonimo di Giulio Mozzi. Chissà come si sarebbero comportati davanti ai testi di Alberto Caeiro, Alvaro de Campos, Ricardo Reis, e soprattutto di Bernardo Soares: i celebri eteronimi di Fernando Pessoa. Forse editore e curatore hanno scambiato Carlo Dalcielo per una sorta di Kakà al contrario, come se Ricardo Izecson dos Santos Leite fosse Giulio Mozzi, e Kakà, il suo soprannome meno celebre, messo tra parentesi.

Insomma, Giulio Mozzi si è travestito, per poco, da Carlo Dalcielo. Ma Carlo Dalcielo è qualcosa di più, su questi temi è facile smarrirsi, come ha fatto Bernard Henry Lévy, citando Jean Baptiste Botul, filosofo inesistente. L’eteronimo scende in profondità nel fittizio, ha una propria personalità che, sebbene dispersa dentro l’ortonimo, riaffiora nitida, gli permette di scrivere, anche in modo diverso. Può sembrare un argomento frivolo, ma un’epoca che, teoricamente, ha fatto della liquidità identitaria uno dei propri fondamenti – tra blogger, nickname e avatar – Carlo Dalcielo messo tra parentesi mi delude, tanto che, quando Mozzi ha cercato di postare il profilo di Carlo Dalcielo in Wikipedia, i gestori hanno cancellato la voce, perché Carlo Dalcielo è autopromozione commerciale.

Ma allora, non siamo tutti Carlo Dalcielo? Forse, visto che le opere non bastano, Lorini e Mozzi dovrebbero definire meglio la vita di Dalcielo. Stabilire, come ha fatto Pessoa con i suoi eteronimi, i dettagli dell’esistenza, anche la morte di Dalcielo, magari prematura, in un incidente automobilistico, un lunedì sera, di ritorno dalla presentazione di un libro, oppure investito da un autobus, mentre Dalcielo attraversa la strada, sorseggiando una bottiglietta di acqua minerale. Lo stile di Carlo Dalcielo sembra il primo Giulio Mozzi. Questa può sembrare una debolezza, e forse lo è. Ma con il primo Giulio Mozzi, intendo Giulio Mozzi a vent’anni, quando magari neppure scriveva. Carlo Dalcielo è come una rigenerazione attraverso la scrittura, un autoritratto di Giulio Mozzi ventenne. Carlo Dalcielo scrive come Giulio Mozzi quando non scriveva. Dovremmo fare sempre così. Giulio Mozzi usa Carlo Dalcielo come una macchina fotografica, per cogliere, come direbbe il fotografo Guido Guidi, le cose là, dove non sono pensate: nel loro farsi immagine.

Pubblicato su Repubblica, 11/2/2010

Domenica 23 agosto alle 21.30, a Dueville (Vicenza) presso il Busnelli Giardino Magico, Bruno Lorini e Giulio Mozzi presentano Il pittore e il pesce. Una poesia di Raymond Carver, un’opera di Carlo Dalcielo. Letture, video, videoletture e wordmix. Organizza: Dedalo furioso.

Domenica 24 maggio a Padova, dalle 9 di mattina a mezzanotte, nell’ambito della terza edizione della Giornata dell’ascolto, l’opera Il pittore e il pesce, nella sua nuova veste video, con le letture registrate a Pordenonelegge, sarà al Teatro delle Maddalene, via san Giovanni da Verdara 4.

Filed under: Notizie

Un nuovo progetto di Carlo Dalcielo.

di giuliomozzi

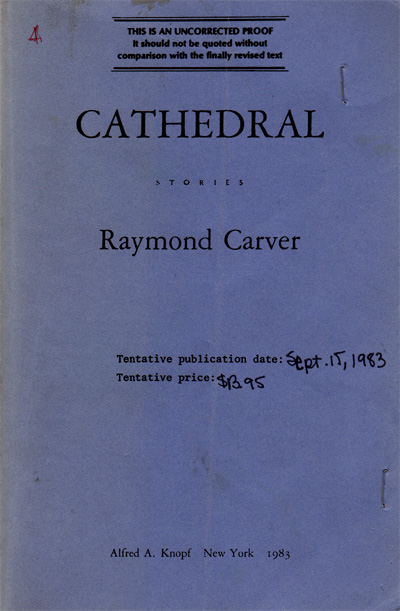

Qualche giorno fa, a Minneapolis, per la modica cifra di ottanta dollari, presso James & Mary Laurie Booksellers, 921 Nicollet Mall, ho acquistato questa copia di Cathedral di Raymond Carver. Si tratta di una prova di stampa non corretta, di quelle che le case editrici preparano per inviarle ai giornalisti con largo anticipo sulla pubblicazione del libro, in modo da poter avere delle recensioni non appena il libro finito sia in libreria.

Alcune copie possono essere firmate dall’autore (con dedica a certi giornalisti o critici ecc.). La mia copia non è firmata, e ciò ne giustifica il basso prezzo (una copia firmata può arrivare fino a 450 dollari, vedi qui).

Di solito tra queste prove di stampa non corrette e le stampe definitive ci sono differenze minime: qualche refuso corretto, qualche virgola spostata e così via. Adesso dovrò trovare il tempo di fare il confronto con la stampa definitiva, per togliermi la curiosità.

Per il momento, colloco questo oggetto accanto all’edizione originale di The Painter and the Fish, nello scaffale dei cimeli carveriani.

Filed under: Notizie | Tag: Il pittore e il pesce, North Dakota University, Raymond Carver, The painter and the fish

[dal sito della North Dakota University, sezione news.]

Please join the English Department as Giulio Mozzi reads from his fiction and also gives a presentation on the artwork and fiction tied to his fictional author, Carlo Dalcielo. Mozzi has published over 20 works of fiction, poetry, and edited volumes with prestigious Italian presses like Einaudi and Mandadori. His prize-winning collection, Questo e’ il giardino (This is the garden) is being translated by UND faculty member Elizabeth Harris Behling. Mozzi and Harris Behling will give a joint reading and presentation at the North Dakota Museum of Art at 4 p.m. Wednesday, Oct. 22, in the North Dakota Museum of Art. A reception will follow. — English.

Filed under: Rassegna stampa | Tag: Il pittore e il pesce, Pordenonelegge, Raymond Carver, The painter and the fish

Leggi l’articolo apparso il 9 settembre 2008 nel quotidiano Il Brescia.

Filed under: Opera | Tag: Il pittore e il pesce, Pordenonelegge, Raymond Carver, The painter and the fish

Allestimento e foto di Bruno Lorini.

Filed under: Contorni | Tag: Il pittore e il pesce, Pordenonelegge, Raymond Carver, The painter and the fish

Foto di Bruno Lorini.